Whether you’re writing a long white paper or short bits of copy for a bunch of Google Ads, your words need to do more than simply tell: they need to persuade.

Marketing is about persuasion.

The entire point of marketing is to convince others to agree with a proposition while motivating them to take whatever action best serves your strategic goals. Everything we do as marketers is intended to influence enough people to buy the product, click the link or hit subscribe – or at least remember the brand as worthy of consideration.

Yes, I do have this problem or need. Yes, this product does look like the perfect solution. Yes, I should act now to avoid missing out.

But talk of persuasion can leave some marketers feeling icky or uncomfortable, as if it’s somehow synonymous with manipulation. The persuasive arts are a powerful tool and, like the Force in Star Wars, there is a dark side – what the Ancient Greeks termed sophistry: “the use of clever but false arguments, especially with the intention of deceiving”.

And, like politics, marketing is no stranger to sophistry. It’s why we have the Australian Trade Practices Act. But persuasion can and should be honest and factual if your brand is to retain any credibility with an audience that doesn’t appreciate being taken for a mark.

Note that I said honest rather than truthful. The question of whether brand X is really better than brand Y is almost always subjective. You can’t state it as a true fact, but you can honestly put forward the reasons why you believe it to be true.

And if your reasons make sense, then the person reading your copy may be persuaded to find out if the same is true for them.

In short, it’s not enough to simply state the features of your product or service and assume people will automatically be interested. The aspects you highlight and those you leave out, the use cases you describe, the evidence and proof points you provide, even the very words you choose to evoke certain reactions in the reader will likely be because you believe they make the best impression on the right audience.

That’s persuasion. And, like most things these days, there’s a framework; except this one is over 2,300 years old.

It’s all Greek to me

The Greeks didn’t invent persuasion, which is as old as communication itself.

But what the Greeks did do was elevate persuasion to a practised art; analysing, refining and codifying the most effective techniques. And while they were mostly concerned with the spoken word – writing being a relatively new technology – the same rules of rhetoric are just as useful today when crafting persuasive copy or content.

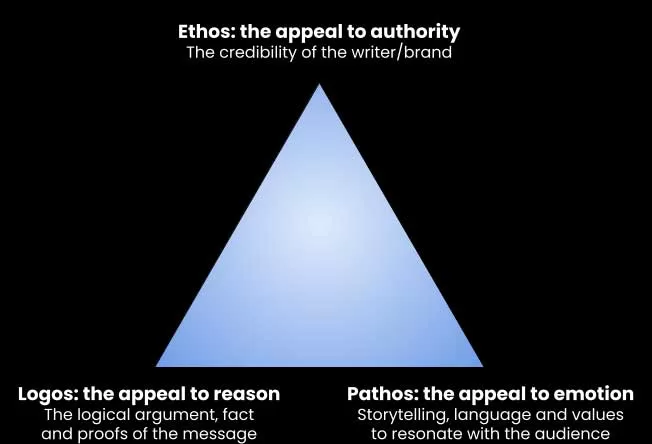

There are many schools of thought when it comes to rhetoric, but I feel Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle – consisting of his three essential appeals – is the best introduction for marketers looking for a simple and practical framework that can be easily applied in most scenarios.

1. Ethos: The appeal to authority

This one is all about the credibility of the speaker or writer. In a nutshell, it’s the “Why should I listen to you” bit.

You’d accept medical advice from your doctor over your neighbour (or at least I would hope so). That’s not to say your neighbour doesn’t have anything worth saying or that a doctor isn’t capable of occasionally getting things wrong. It’s just that the weight you give to a piece of advice will, or should, be coloured by how much expertise and authority you believe the other person has on the topic.

Is your content written by a junior writer curating some quick research from Google that just about anyone else could have done? Or is it written by genuine subject matter experts capable of providing valuable insights drawn from years of demonstrable experience? That’s ethos.

2. Logos: the appeal to reason

This is the message, laying out the information and evidence in a logical progression that takes the audience from the initial premise all the way through to your intended conclusion.

The perfect example of Logos in action is the courtroom: two lawyers arguing innocence or guilt based on the same pool of evidence. Each side attempts to frame the same evidence as either irrelevant or crucial to understanding the case. The jury then determines if one side or other has persuaded them of their argument beyond reasonable doubt. Which version of events makes the most sense.

For marketers, Logos means structuring your copy and setting out your propositions to put forward the best possible case for why the reader should agree with your premise or consider buying your product. And, just as in court, you need to provide evidence wherever possible to back up your claims; stats, case studies, testimonials and other proof points.

3. Pathos: The appeal to emotion

Thirdly, your copy needs to resonate with the audience on an emotional, as well as a logical, level. While Logos appeals to the brain, Pathos appeals to the heart, or gut. Does the conclusion feel right? Does the copy lead the audience to like the brand behind the content? Does it motivate them to act?

While we all want to believe we make decisions based purely on rational thinking (Logos) we’re far more motivated by emotion than we would often like to admit. Whether you like or dislike – or are merely indifferent – about a brand or a piece of content can have a huge impact on your final decision.

SImilarly, facts don’t move or persuade us nearly as much as people do. We can relate more easily to the story of someone else’s experience than we can to any number of cold, hard facts. That’s an emotional connection.

Imbuing your copy with emotional language and imagery or weaving stories and anecdotes into your content also aids memory and recall. For example, a little humour can be a great tool to maintain a reader’s attention, while even mild enjoyment can increase pleasure hormones like dopamine in the brain, which aids in the creation of memories.

A fourth appeal: Kairos

While not included in Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle, there’s a fourth rhetorical appeal that can be just as important to persuasive copy: Kairos.

Kairos comes from the Greek for timeliness or opportunity and is concerned with the timing of your argument. In short, this is about the right message at the right time. Marketing spruiking the warm comforts of winter woollens is unlikely to persuade too many people in the middle of a summer heatwave. But that same marketing might still be successful if it targets families and thrillseekers about to fly overseas for their annual skiing holiday.

Timeliness can also be extremely persuasive when combined with a strong call to action. For example, the standard call to action of “Act now while stocks last” works on a number of rhetorical levels. It contains a logical appeal; there’s only so much stock available so a sell-out is possible. The inferred FOMO also gives the call to action an emotional appeal. And the framing of a limited time window for the opportunity gives the call to action its urgency; kairos.

Have I persuaded you?

When writing your copy or planning your content, always have these four persuasive appeals at the back of your mind.

- Why should they listen to me/the writer?

- What will convince them to agree with my premise?

- How can the copy resonate with the reader on an emotional level?

- When will this message be at its most timely?

The study of rhetoric goes much further than these four appeals, of course. These four are merely a good place to start when crafting persuasive copy or content.

There are numerous rhetorical terms to describe all kinds of linguistic devices and flourishes to capture and hold an audience’s attention. And, to be honest, many of us use rhetorical techniques every day without realising it.

But your copy needs to be intentional. You need to rely on more than just your gut to understand why one piece of content works better than another or which call to action is likely to drive more conversions.

As you seek to persuade more customers with your marketing, how will you make every word count?